Rowan Castle - Travel & Photography

© Rowan Castle 2019

India and Pakistan 1996 - Diary (Page 3)

We cycled through the grounds of the municipal building and then I was

dropped off at what I took to be the town hall. I thought that there had been

some mistake, I was expecting the Golden Temple, but was instead confronted

with a large white marble building with a clock tower. However, there was no

confusion, this was the outer facade of the building, the Golden Temple itself

and the Akal Takhat (the Sikh Parliament building) were within it's walls.

At the entrance, I removed my boots and socks and covered my head with one

of the head cloths provided. I was then able to pass through the gateway of the

white outer building and emerge into the inner courtyard. There, nearly filling

the enclosure was the revered 'Pool of Nectar' or Amritsar which had given the

city it's name, and in the middle, illuminated by four massive floodlights, was

the Hari Mandir, the Golden Temple. The gold leaf covered domes of the sacred

structure reflected the light in a blaze of colour, which was mirrored on the

surface of the inky water. I rapidly arrived at the conclusion that the Hari

Mandir is easily as beautiful as the Taj Mahal and equally worth visiting. I

slowly made my way right round the edge of the pool, walking barefoot either

on the cool marble or on the rough hessian walkway that had been laid down in

places. I knew that I would be returning the next day for a longer visit, and so

having completed my circuit, I rejoined my rickshaw driver in the street

outside.

It had been a tiring but enjoyable day, and I was looking forward to exploring

Amritsar in greater detail.

Day 34 - Tuesday 6th August.

At nine in the morning, I returned to the Golden Temple, travelling by

cycle rickshaw. As I passed once again through the outer white marble

walls, I noticed plaques which gave the names of Sikhs who had died

fighting in the three wars with Pakistan. In more recent years however, it

has been the temple itself that has been the scene of violence and

warfare. In 1984, the temple was occupied by Sikh extremists, lead by one

Jarnail Singh Bhindranwhale (Jarnail may be a corruption of the English

word General). They were calling for the Punjab to become a separate Sikh

homeland, to be called 'Khalistan'. The Indian Prime Minister of the time,

Mrs. Indira Gandhi came under great pressure to act swiftly and firmly

against the separatists and she responded to the emergency with

'Operation Bluestar', in which army tanks invaded the temple and opened

fire. The fighting lasted for two days and killed thousands of Sikhs inside

the grounds of the temple. For Indira Gandhi, invading the Sikh's most

sacred building meant almost inevitable death, due to the outrage that it

caused among the Sikh community. Sure enough, on October 31st, 1984 she

was shot dead by her two Sikh bodyguards, as she walked from her house

to her office. However, the killing did not end there. When news of the

assassination reached the streets of New Delhi, fanatical Hindu mobs ran

riot, intent on revenge. They murdered Sikhs and ransacked their homes,

leaving at least one thousand people dead by official accounts alone. The

temple was occupied again by extremists in 1986.

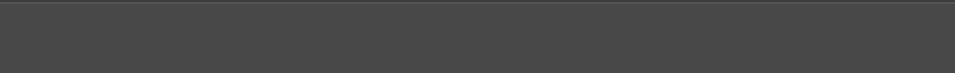

The Golden Temple at Amritsar.

As I walked round the Pool of Nectar that morning, scaffolding was still in

place while repairs to the temple were made; replacing gold-leaf and stone

work which had been damaged by bullets during its recent turbulent

history. Indeed, the Sikh parliament building which stands opposite the

temple at the end of the Guru's Bridge was brand new, the original having

been destroyed by tank fire in 1984.

Now that I was visiting in daylight, I was able to photograph the Hari

Mandir, with it's gold leaf gleaming in the sunlight. Again, I walked all the

way round the Pool of Nectar and took photographs from every angle. On

the way, a British-Indian couple from Birmingham asked me to take their

photograph using their camera, while they stood in front of the Hari

Mandir. I made my way across the Guru's Bridge, and entered the temple

itself. Hidden under a pink shroud inside, was the original copy of the Sikh

holy book, the Granth Sahib. This was presided over by several temple

officials who sat around the shroud in a small group. Continuous readings

are made from copies of the book and these are relayed over a public

address system so that their careful and reverent recitals echo from the

cool marble walls. Having filed in and out again, I ended my second and

final visit to the remarkable temple and returned to the street outside to

find my rickshaw driver.

The Golden Temple, Amritsar.

From there, I went to the site of one of the most shameful episodes in

British history, which is now a serene garden in the centre of Amritsar. In

March 1919 the British government passed the Rowlatt Acts, which were

designed to stamp out sedition within India by a series of repressive

measures and curbs on the rights of Indians. After protests in Amritsar

against the acts, the commander of the British troops stationed in the

area, Brigadier Reginald Dyer, banned all public gatherings of any kind.

That day, 13th April, he learnt that a protest rally was to be held in

Jallianwala Bagh (Bagh means garden). By the time Dyer arrived at the

walled garden (which was accessible only via a thin alley way), it was

crowded with ten thousand men, women and children. The narrow

entrance prevented him from deploying his armoured cars and so instead

he marched his troops into the park, arranged them into a line, and

ordered them to open fire. The troops fired for ten minutes and discharged

1650 rounds of ammunition into the throng, killing around four hundred

Indians and wounding twelve hundred. The only exit to the garden was

blocked by the troops, and in their desperation to escape, many jumped

down the well which stands in one corner of the enclosure.

Among the crowd that day was a young Sikh boy who had volunteered to

hand out water during the meeting, and after the atrocity he vowed to

avenge the massacre at any cost. His name was Udham Singh and before I

set out for India I had watched a fascinating television documentary about

his life. When he reached adulthood, he set off for England to put the first

part of his plan of revenge into effect. The Governor of the Punjab at the

time of the Amritsar Massacre was Sir Michael O' Dwyer, and he had whole-

heartedly approved of Dyers actions that day. On arrival in Britain, Udham

Singh shaved his beard and cut his hair (both acts forbidden to Sikhs) and

got a job as one of O' Dwyer's servants. He even pretended to become a

good friend of O' Dwyers and appeared to get on well with him. On

Wednesday 13th March 1940, Udham Singh fulfilled his vow to avenge the

deaths at Amritsar. He attended a joint meeting of the East India

Association and the Royal Central Asian Society, at which Sir Michael O'

Dwyer, Lord Zetland (Secretary of State for India), Lord Lammington

(former Governor of Bombay) and Sir Louis Dane (former Under-Secretary

to the Governor of the Punjab) were all present. As the meeting neared its

end, Udham Singh rose from his seat and walked calmly towards the

speakers platform. Without warning he produced a pistol and fired six shots

at the dignitaries in front of him. Sir Michael O' Dwyer was killed, while

Lord Zetland, Sir Louis Dane and Lord Lammington were injured. Udham

Singh was eventually found guilty of murder and hanged at Pentonville

Prison. In 1974 his remains were exhumed from their prison grave and

returned to India, where he had been hailed as a martyr and where he

received a hero's funeral.

The garden is still reached via the narrow alley, but that is one of the few

features that remains unchanged from 1919. The wasteland that was

Jallianwala Bagh then, has been transformed into a carefully tended public

memorial garden to those who were killed in the massacre. Near the

entrance stands a small tetrahedral stone block, on which is the simple

inscription "People were fired at from here". While at the far end of the

park a tall sandstone cenotaph commemorates the dead. I walked over to

the building that houses the well, which still stands, and peered down the

shallow shaft which has long since been filled in with mud. Bullet holes are

said to remain in the walls of the well building, but I did not see any. A

small building near the entrance houses the Martyr's Gallery which holds

the portraits and histories of several leading political campaigners of the

time who had either been hanged by the British or transported to the penal

colony on the Andaman Islands. The portrait of Udham Singh was also

present. Fixed to the fence near the entrance is a notice which provides a

constant reminder of the terrible crime that was committed by the British

in 1919 it reads:

"This place is saturated with the blood of about two thousand Hindu,

Sikh and Muslim patriots who were martyred in a non-violent struggle

to free India from British domination. General Dyer of the British Army

opened fire here on unarmed people. Jallianwala Bagh is thus an

everlasting symbol of non-violent and peaceful struggle for freedom of

Indian people and the tyranny of the British. Innocent, peaceful and

unarmed people who were protesting against the Rowlatt Act were fired

upon on 13th April, 1919. Under a resolution of the Indian National

Congress this land was purchased for Rs. 565,000 for setting up a memorial

to those patriots. A trust was formed for this purpose and money collected

from all over India and foreign countries.

When this land was purchased, it was only a vacant plot and there was no

garden here. The trust requests the people to observe the rules framed by

it and thus show their reverence to the memorial of the Martyrs.

S. K. MUKHERJI

Secretary

Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial Trust."

Leaving the garden, I asked Januk, my cycle rickshaw driver to take me to

the statue of Udham Singh that he had pointed out on the way to the

Golden Temple. The statue stands in the centre of a small roundabout not

far from Jallianwala Bagh. The respect accorded to the memory of Udham

Singh could easily be judged by the presence of a fresh garland of flowers

around the statue's neck.

After a visit to the Amritsar General Post Office to send some postcards to

friends at home, I asked Januk to take me to Ram Bagh; gardens which

were laid out by the famous one-eyed Sikh ruler of the Punjab, Ranjit

Singh. During his reign he was a staunch ally of the British East India

Company, even after they used the rather underhand tactic of sending him

a gift of horses on a barge up the River Indus so that they could chart it at

the same time. The British did not add the Punjab to their territory until

ten years after his death in 1839.

In the centre of the beautiful gardens was a small but interesting museum

exhibiting prints of scenes from the most famous British battles in the

Punjab, paintings of Ranjit Singh, coins from his reign and an assortment of

weapons.

Returning to Mrs. Bhandari's Guest house, I spent a relaxing evening

swimming in the pool, writing my diary, and listening to my walkman. At

dinner, a Belgian couple asked if they could share my taxi to the border

with Pakistan the next day, and of course I agreed. I found that talking with

them about our proposed journeys in Pakistan lifted my spirits a lot. By this

time I had been on the road for just over a month and my energy was

beginning to flag, but now the thought of a new country, and all of the

places that I planned to go once there, renewed my enthusiasm

considerably.

It was the end of my last full day in India and so far the trip had gone much

better than expected, but I knew that the next day I would be crossing one

of the most politically sensitive borders on Earth. If I was refused entry to

Pakistan for any reason, or if a political row between the two countries

closed the crossing point, my whole plan for the journey would be thrown

into disarray.

Day 35 - Wednesday 7th August.

There is only one point on the entire Indo-Pakistani border where travellers

with the necessary visas can cross legally: from Atari in India (near Amritsar) to

Wagah in Pakistan (near Lahore). There are two ways in which the short journey

can be made, the first is by train from Amritsar to Lahore and the second is to

take a taxi to the border and then cross on foot. Originally I had intended to

take the train, but eventually decided to take my travel guidebook's advice and

go by road, which would theoretically take less time.

I got up at seven, had breakfast and then settled my bill with the affable guest

house manager. At ten o' clock the taxi arrived and myself and the couple from

Ostende got in and began our journey to the border. Leaving Amritsar, the road

headed directly west, through brilliantly green fields. Immediately, there were

signs of the sinister nature of the area we were entering. I noticed that the

road was a little wider than might be expected and remarkably free of

potholes, this would presumably make it easier to quickly move troops and

tanks to the border in the event of a war. The smooth tarmac made our journey

quiet and comfortable and we only occasionally had to slow when small herds of

cows or water buffalo strayed across the road. I noticed that it felt very strange

to be a passenger in a car after a month of travel by auto-rickshaw. Very soon

the heavy military presence was palpable, side roads branched off to army

barracks and once or twice to an Officer's Mess.

The start of the border zone was marked by a simple white gate across the

road. A soldier at a desk examined my passport and handed me a slip of paper -

my 'gate pass'. I had to change any Indian Rupees that I was carrying to Pakistani

Rupees (Indian Rupees cannot legally be taken into or out of India) and I was

then allowed to proceed on foot to the customs post, a small hall located

further west along the road.

The staff at the customs post were not very friendly or speedy. It took an age to

get the Sikh soldier behind the desk to look at my passport and then he asked

me to fill in a form but would not even lend me a pen. Eventually he quite

literally threw my passport back in my face and motioned me towards a metal

detector and X-ray machine on the far side of the hall. More waiting, and then

the 'gate pass' sentry re-appeared and demanded to re-examine everyone's

passports. He scribbled something extra onto each of our gate passes and then

disappeared. This performance was repeated at least two more times.

After a long wait, I was asked to empty all of my pockets and then I was

scanned with a handheld detector wand. The soldiers told me that I could

gather up all of my possessions, and then asked me to do the entire operation

again! They made a cursory search of my backpack and then I was allowed to

carry on up the road.

I was now approaching the border proper. I had to cross over to the other lane

of the road, because the one that I had been walking on was now blocked by a

massive barricade of razor wire. Up ahead were the two sets of border posts,

one Indian and one Pakistani. The Pakistani one was painted with the slogan

"Long Live Pakistan!" in enormous Islamic green letters. As I approached I could

see very tall fences to either side, topped with razor wire and flanked on both

sides by grim looking sentry towers.

The history of the border is as ugly as it's modern appearance. As British rule in

India came to an end, the British reluctantly gave in to Muhammed Ali Jinnah's

demands for a separate homeland for India's Muslims and were forced to

partition the country. The problem they faced was to draw up a border which

would successfully divide the country, leaving Hindu majority areas on one side

and Muslim majority areas on the other. Jinnah and Nehru (India's nationalist

leader) both realised that they could never agree the border between

themselves and so instead they asked the British to settle the matter with a

boundary commission, to be headed by an English barrister. The task was given

to Sir Cyril Radcliffe and he had only a matter of weeks to decide where the

boundaries should be drawn. When Independence came and the boundaries

came into effect, the inevitable result was chaos and a humanitarian tragedy on

a huge scale. Hindus and Sikhs who found themselves on the Pakistani side of

the border fled one way, and Muslims on the Indian side fled the other. It was

the largest transfer of people in history, and as mobs from religiously opposite

communities on both sides of the border slaughtered the refugees on their long

marches, it is believed that as many as 500,000 people may have been killed

trying to cross the Radcliffe line, which I was about to step over, forty nine

years later.

At last I came to the actual border itself; the focal point of the strange no

man's land that I had been walking through for the previous few minutes. It was

marked by a white line which ran across the road and was continued through

the bushes on either side as a very low white wall. On one side of the line stood

an Indian sentry and on the other, a Pakistani, who was armed with an AK-47. I

stepped across the line, shook hands with the Pakistani sentry and presented

my passport. I was told to continue down the road and stop at the Immigration

office. It was there that I was met by a group of policemen, who could not have

been more friendly. I had to fill in a few details in the police book and then I

was sent further down the road again to the customs post. There were no

problems there either, they had a quick rummage through my backpack but

were mainly interested in making sure that I was not bringing any alcohol into

the country. At last I came to the final stage of the border and the end of one of

the strangest experiences of my life. The Pakistani gate was the last

checkpoint, at which I had to show my passport and Pakistani visa for a final

time and then I stepped out of the border area and into Pakistan proper. It was

exactly two years to the day since I had stood on top of the fifteen thousand

four hundred feet high Naltar Pass in Northern Pakistan during the trekking

expedition I had taken part in on my first visit to the country. It seemed to me

incredible that I had been able to return so soon, and I felt, a real

achievement.

I may have arrived in Pakistan, but my border problems were far from over. A

taxi was waiting for custom as I emerged from the gate, I climbed in and we

moved off towards Lahore, having agreed a price of Rs 600. We had not gone

very far along what was quite obviously the main road to Lahore when we

suddenly veered off along a side lane. I feared that I was about to be ambushed

and robbed, anxiously I asked the driver where abouts we were going. However,

there was no need for alarm, the road turned out to be a short cut, and soon

we had rejoined the main road, heading west once more. We drove over a

railway crossing and then alongside a wide brown canal where local children

were swimming and playing, before the countryside merged almost

imperceptibly with the outskirts of Lahore.

I had asked the driver to take me to a fairly cheap hotel in the centre of town,

but I did not know at that point that it had closed down, and as a result the

driver had no idea where it was. First he took me to the Pearl Continental, the

most expensive hotel in Lahore, with prices that were well out of the range of

my budget. Next we drove all around central Lahore, getting stuck in the most

appalling traffic jams and the taxi driver asked directions at every opportunity

but seemingly to no avail. Eventually, we arrived at the hotel and realised that

it had closed down a long time ago. In desperation, I asked to be taken to a

more expensive hotel that was at least on a fairly major road in the city centre.

I arrived at the Amer hotel, easily the biggest and most luxurious hotel of the

journey; small fountains played in the lobby and the whole place was kept

fantastically cool by air conditioning. Now I had only one more problem to

overcome before I could relax, I only had a few Pakistani Rupees left, and so I

set off for the American Express building.

When I got back, I relaxed in my hotel room which had a television, telephone,

bathroom and was air conditioned like the rest of the hotel. The main TV

channel alternated between broadcasting CNN, BBC World and its own

programmes, as well as the call to prayer at the appropriate times of day. I had

Chicken Jalfrezi for lunch in the hotel's excellent restaurant and in the evening,

I phoned home to let my parents know that I had crossed the border.

Day 36 - Thursday 8th August.

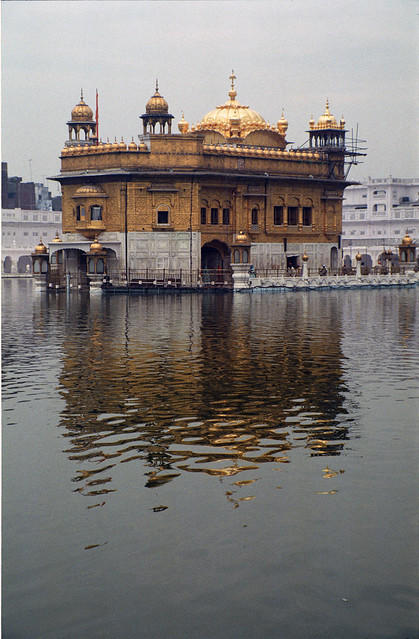

I set off to explore the city at 8 a.m., and went first to see the great cannon

Zam-Zammah which stands in the centre of the road, opposite the Lahore

Museum. The gun was the setting for the opening paragraph of Rudyard Kipling's

famous novel Kim which begins:

"He sat, in defiance of municipal orders, astride the gun Zam-Zammah on her

brick platform opposite the old Ajaib-Gher - the Wonder House, as the natives

call the Lahore Museum."

The cannon is cast in copper and bronze and was used by the Afghan Duranis,

the Sikhs, and was deployed in the battle of Panipat (north of Delhi) in 1761.

Zam-Zammah Cannon, Lahore, Pakistan.

I continued along the noisy circular road, passing cages of bright green

parakeets for sale, and crossed over into Iqbal Park. In the centre of the park

stands the Minar-i-Pakistan, a tall concrete tower which was built in 1960 to

commemorate the 23 March 1940 signing of the Pakistan Resolution by the All

India Muslim League, which called for a Muslim state separate from India. I took

the opportuntity to climb the spiral staircase to the top of the tower, where I

enjoyed superb views across the city.

Retracing my steps and setting off down a side street opposite the park, I came

to the entrance to the splendid Badshahi mosque, one of the largest in the

world. I stepped through into the spacious courtyard, surrounded by high

sandstone walls. Directly infront of me was the mosque, with its three high

white marble domes brilliant in the sun. It was built in 1676 by the Moghul

Emperor Aurangzeb, and used to overlook the river Ravi before the water

changed course and moved to its current position. The courtyard was so hot in

the sun that my feet were burning even through my thick walking socks, and I

was relieved to leave the enclosure for the cool darkness of the high vaulted

sandstone interior. By now I had a local guide, who on the way back out pointed

to the repairs being carried out to the entrance wall. Apparently the stone had

had to be purchased from Jodhpur in India and transported by road across the

border point that I had passed through the previous day.

Badshahi Mosque, Lahore.

Directly opposite the entrance to the mosque stand the impressive ramparts of

the Alamgiri gate to Lahore fort, and it was there that I went next. The fort was

rebuilt into its current form by the Moghul Emperor Akbar in 1566, but was

damaged by the Sikhs and the British. I strolled around the mainly crumbling

ruins of the forts buildings and palaces for quite a while, and I found that there

were several features of particular interest. One was a huge jal (a carved

lattice screen) which had been crafted from a single piece of marble. The other

feature was the Shish Mahal (palace of mirrors) which was under repair but had

a beautiful reflective, many faceted ceiling, similar to the one I had seen at the

Amber Fort in Jaipur. As I walked round, I was reminded of the book To The

Frontier by Geoffrey Moorhouse, which describes his journey around Pakistan in

1990. In the book he recounts a conversation with a man who had been a

political prisoner in the time of General Zia's rule, Pakistan's last military

dictator. The prisoner had explained to Moorhouse how tourists had been

happily looking round the public part of Lahore fort, while he and other

political detainees were being brutally tortured in the cells below, often until

they were close to death. This presumably occurred up until 1988 when Zia was

killed in a mysterious plane crash.

Lahore Fort, Lahore.

It was time to book my ticket out of Lahore, which meant standing in several

lengthy queues at the railway reservation office. The small hall was hot,

crowded and all of the signs were in Urdu. It took a while for me to realise how

the system worked, and even then I wasn't totally sure that I understood what

was going on! Eventually, I managed to book a first class ticket which would

take me to Multan.

The next task was a trip to the Alvari Hotel where, according to my guidebook, I

would be able to buy items like razors, deodorant, and 'AA' size batteries which

I was running low on by this stage of the journey. I got everything I needed, but

unsurprisingly the cost was astronomical.

Returning to the hotel, I rested in the wonderful cool of my air conditioned

room and had lunch in the restaurant. I was brought out of my relaxed state by

the realisation that I was running out of Pakistani Rupees and that the American

Express building was about to close. I set out to get there as fast as possible.

Emerging from the air conditioned hotel, the heat of the day initially always hit

me like a mallet, the temperature being around 35 Centigrade in the shade.

However, it was amazing how well I had acclimatized after a month in the

tropics and sub-tropics, and I found that I could actually run to the American

Express office without any ill effects. It occurred to me that for a long time now

I had not really been noticing the fierce heat that I had been living in day in and

day out. Unfortunately, my level of acclimatization was about to be pushed to

the limit, during the next part of my journey which would be further south in

Multan.

On the way back from cashing my traveller's cheques I visited the 'Wonder

House', the Lahore Museum. Inside I found a fascinating collection of carpets,

tile work and miniature paintings as well as examples of the carved doors and

balconies which used to be found in the bazaars of Lahore. One item in

particular held my attention for many minutes: a beautiful Chinese ivory chest

that was carved with a multitude of figures, animals and trees with a precision

that defied belief. The museum's most famous exhibit was equally compelling,

it is a small carved statue of Buddha in a state of fasting. The sculpture was so

well done that the veins of the subject stick out from its skin, its sunken eyes

are cleverly hidden in the shadows of its eye sockets and yet the face radiates a

peaceful and tranquil expression. Also impressive was the museum's collection

of photographs and other items detailing the history of Pakistan and its

independence. Although the purpose of much of it was as morale boosting

propaganda, I was fascinated by the story of one of Pakistan's military heroes,

displayed in the collection. He had been a young pilot in the Pakistani Air Force

and had taken off from an air base near the border with India in a two seat jet

training aircraft, with his instructor in the back seat. Without warning the

instructor took control of the aircraft and tried to fly it over the border and

desert to India. The young pilot quickly realised that Pakistan was about to lose

both an experienced pilot and a valuable jet to a hostile country and responded

by wrestling with the controls and forcing the jet to crash into the ground. Both

pilots were killed instantly, and the young hero was posthumously decorated for

bravery. Included in this section of the museum was the mangled tail fin from

an Indian jet fighter that had been shot down in the Indo-Pakistan border war of

1965. It was during this conflict that the area I had just passed through,

between Amritsar and Lahore, was turned into a battle zone. The war ended in

defeat for Pakistan, and by then Indian tanks had rolled to within a matter of

miles of the suburbs of Lahore.

The statue of the ‘Fasting Buddha’, Lahore Museum.

Back at the hotel, I spent the evening watching the BBC World channel on the

television. As far as I could gather this was picked up from a satellite by a local

TV station and re-broadcast terrestrially at certain hours of the day. It was very

strange to watch adverts for the Holiday programme in the middle of Pakistan,

and the channel also reminded me how far I was from home, when Bill Giles

appeared and delivered the weather forcast in front of a map that showed India

and the whole of South-East Asia. The broadcasting then switched from BBC

World to Pakistan Television which was showing live coverage of the England v

Pakistan test match which was being played back in Britain. The match was

punctuated by adverts (in Urdu) for agricultural pesticides. Even stranger than

seeing adverts for industrial pesticide was watching the adverts for cigarettes

made by Wills, sponsors of the test match. The biggest suprise came when the

broadcasting switched back to CNN, and I noticed that whenever a program

featured a couple kissing, their faces were suddenly blurred. The channel was

being re-broadcast with a slight time delay so that some official could quickly

censor anything considered inappropriate. Even the most innocuous scenes were

sometimes considered too much, for example, during one news clip President

Clinton kissed a female conference delegate on the cheek, and the scene was

hurriedly scrambled.

Sitting there watching the test match, it was possible at times to believe that I

was back at home, but this feeling was easily dispelled whenever there was a

power cut, the air conditioning shut down and the temperature suddenly soared

in the darkness of my hotel room, proving that I really was in Pakistan.

Day 37 - Friday 9th August.

Reading the morning's English newspaper, I learnt that the day before at 8 p.m.

there had been an earthquake in Pakistan that had measured five on the Richter

scale. The epicentre had been in North East Punjab, about 150 km from

Peshawar and it had been too far away to feel any tremors in Lahore.

At ten, I got an auto-rickshaw to take me to the famous Shalimar gardens in the

north east of the city. The roads in the vicinity of the gardens were in an

extremely bad state, and I was thrown around in the back of the rickshaw for

many minutes before we finally arrived at the entrance, on the famous Grand

Trunk Road. The Shalimar Gardens were set out by Shah Jehan sometime around

1640, and are one of the few surviving examples of their kind. When I arrived I

was disappointed to find that all of the pools were empty, although the

fountains were switched on briefly at the start of my visit. I recognised one of

the architectural features from the palace at Jaisalmer; a waterfall had been

engineered and recesses carved into the marble panel behind it. When used

originally, each small carved alcove contained an oil lamp, so that the lights

would have danced and flickered through the flowing water. Despite recognising

this feature, it was difficult to imagine the beauty of the garden as seen in

Moghul times, but it was a tranquil place to walk round - away from the noise

and bussle of the rest of the city.

Shalimar Gardens, Lahore.

Once back on the Grand Trunk Road, I took an auto-rickshaw right across the

city to Jehangir's Mausoleum and on the way I crossed the vast River Ravi by

way of a long high road bridge. The suburb that lay on the other side of the

river was very dusty and mostly made up of basic housing, and after winding our

way down a couple of side roads we pulled up alongside the gateway to a large

walled garden, this was the entrance to Dil Kusha, the grounds of the

mausoleum.

The Moghul Emperor Jehangir ruled from 1605 to 1627, he died whilst in

Kashmir, but had insisted that he be buried in Lahore, and so his body was

transported one hundred and twenty miles to its final resting place near the

River Ravi. His mausoleum was not constructed until ten years after his death,

by his son Shah Jehan (famous for building the Taj Mahal). The mausoleum is a

single storey red sandstone building, decorated with bands and zig zags of white

marble and complimented by four mock minarets, one at each corner. I reached

it by walking through the Dil Kusha, a beautiful park to this day but once a

substantial arboretum boasting many different species of tree. Today, mainly

mango and cherry trees remain. By the time I reached the mausoleum building I

had been approached by a very old man, who was the local guide, and he

showed me around the inside of the tomb. Just inside, were the remains of an

original painted ceiling (which had been very badly damaged by the Sikhs) and

some beautiful tile work. However, the finest feature of the mausoleum was

Jehangir's sarcophagus itself; made of white marble it is decorated with pietra

dura work (which I thought was possibly of a finer quality than that at the Taj

Mahal) and inscribed with the ninety nine names of God. The ceiling above the

sarcophagus is a plaster British replacement of the marble original, which was

looted by Ranjit Singh.

The Mausoleum of Jehangir, Lahore.

The Mausoleum of Jehangir, Lahore, Pakistan.

Rejoining the rickshaw (the driver had agreed to wait for me), we retraced our

route back to the centre of Lahore and weaved our way through the old city to

the beautifully tiled Wazir Khan Mosque. It was built by Sheikh Ilm-ud-Din Ansari

in 1634 (during the reign of Shah Jehan). The courtyard was almost unbearably

hot to walk on, and I was pestered by one of the children who were milling

around, but the visit was worthwhile simply because of the superb

craftsmanship and splendour of the tilework which decorated the mihrab and

the minarets.

Wazir Khan Mosque, Lahore.

Leaving the mosque, I used the digital compass on my watch to walk directly

south through the warren of alley ways that makes up the bazaar in the old city.

Unfortunately, it was a Friday (the Muslim holy day of the week) and so the

little shops all had their shutters down and the normally colourful and bustling

streets were deserted. When I finally emerged on the Circular Road, I headed

back to the Lahore museum to photograph some of the exhibits that I had seen

on my earlier visit, many of the items were so interesting that they merited a

second look in any case.

Back at the hotel, it was time to resolve a problem. A friend of mine, Ahmed

Mudassir Khan, lives in Lahore and was one of the guides from the Adventure

Foundation who had accompanied us on the 1994 trek. During a bus journey in

1994 I had talked to him about the possibility that I might return to Pakistan and

he had said that if I passed through Lahore I would be welcome to visit him. I

had therefore written him a letter about a month before I set out, giving the

approximate dates that I would be in the city and suggesting that we might

meet up if he was not too busy. Unfortunately I had not received a reply and did

not know whether this was because the letter had been lost in the post, he had

moved or that he was too busy with his work. I decided that I should at least try

to get in touch while I was in Lahore and so I went down to the lobby and asked

the receptionist to check if the telephone number had changed. Ideally, I would

have liked to ask him to ring up for me and introduce me in Urdu, since I was

worried that Mudassir might not remember who I was, but I felt that this might

be too much of an imposition. In the end the receptionist himself suggested the

very same thing. He made the call and spoke to Mudassir's mother, he told me

that she had said Mudassir had received my letter, but that he was out at the

moment and would ring back later. When Mudassir returned my call he arranged

to meet me at the hotel at 8 o' clock the next evening.

Day 38 - Saturday 10th August.

It was my last full day in Lahore and I planned to take things at a fairly relaxed

pace. At ten I set out for the Data Darbar Mosque, the grounds of which

encompass the Mausoleum of Data Ganj Bakhsh Hajveri. Data Ganj Bakhsh lived

in the eleventh century and was a very famous Sufi preacher, in fact in modern

Pakistan he is revered as the most important saint in Sufi Islam. During the few

days each year marking his death anniversary, tens of thousands of pilgrims

flock to the mausoleum to pay homage.

On arrival at the mosque I found that it was an extremely modern building, and

the architecture was similar in style to that of the Shah Faisal Mosque in

Islamabad, which I had visited in 1994. The mausoleum was a small building

with a green tiled dome and several fine marble screens, a Qoran reading was in

progress when I arrived and there was a large group of pilgrims sitting in prayer

or respectful silence.

Leaving the mausoleum and mosque, I went back to the old city in an attempt

to find the golden mosque, but soon became disoriented and decided to return

to my hotel. By now I felt that I had seen a good proportion of Lahore's splendid

architecture and bazaars and so I was content to rest until the evening.

Mudassir met me at my hotel room at eight, as arranged. We had a long chat

about my journey up to that point, and I showed him the route that I had taken

on the maps of India and Pakistan that I had in my backpack. Mudassir was

eager to find out how everyone from our trekking party was getting on and I

told him as much as I knew (I had not seen many of them since a re-union meal

a few weeks after our return). It was then time to set off to Mudassir's house for

dinner, but the travel arrangements came as a surprise. I had assumed that we

would travel by car. However, in Pakistan the motorbike is the most common

form of transport and I learnt that Mudassir had left his car at home and

brought his small Honda motorbike instead.

I had never riden on a motorbike before, and as we set off through the busy

streets of Lahore I must admit that I was terrified, particularly because neither

one of us wore a crash helmet. A lot of the time I was worried that we might hit

a large pothole and that I might lose my grip and be thrown off. Gradually, I

began to relax, and as we neared Mudassir's house I was beginning to enjoy the

ride.

Mudassir lives in Gulberg, an affluent suburb of Lahore which is home to most of

the best housing and more or less all of the finest restaurants. We pulled up in a

quiet back-street and I was lead through the front door and into a plush living

room. It was decorated with comfortable fitted carpets and two brass ceiling

fans, which were keeping the whole room marvelously cool. Mudassir told me

that dinner was not quite ready, and so he served tea and biscuits and showed

me some photographs of his recent wedding ceremony. More photographs

followed, this time of the trek to the base camp of K2 (the World's second

highest peak) that he had taken part in the year before. The scenery was

incredible and included in the collection of prints was a photo of Trango tower,

a famous spire of granite, 26,000 ft high, which looms above the approach to

K2. He said that the trek had been very demanding, and that when they had

camped on the glacier at the base camp it was bitterly cold and all of their

equipment was soaking wet.

Mudassir's mother had prepared the meal, but because I was a strange man in

their home she kept herself completely out of sight, in accordance with the

rules of purdah. Occasionally her arm appeared from behind the doorway as she

passed the food and plates through to Mudassir. The meal of chicken, rice, eggs,

yoghurt, spicy mango chutney and mutton meat balls with potato, was delicious

and very filling. During our conversation over dinner, I found out that Mudassir's

family were originally from Afghanistan, and had then migrated to India. When

India was partitioned in 1947, they chose to move to the newly created

Pakistan.

After dinner Mudassir showed me the photographs that he had taken during our

own trek in 1994. He very kindly gave me four of the photographs in which I was

visible. I was extremely grateful, because up until then I did not actually have

any photographs that showed me trekking in Pakistan; I had forgotten to ask

anyone to take a picture of me with my camera during the trek! Next we looked

at more photographs of his wedding ceremony, which were very interesting.

Mudassir pointed out one of his relatives in a group photo, a large man with a

turban and a beard that had been dyed bright orange, and revealed he was a Pir

(an important and revered holy man). One particularly lively photo showed

Mudassir haggling over a glass of milk traditionally offered by the bride's family.

The milk is symbolic, and the price that is finally agreed is the amount of

money that is then given to the bride's family by the groom's family.

It was then time for me to go back to the hotel on the motorbike, but first

Mudassir took me on a miniature tour of the centre of Lahore. We drove

alongside the canal that I had seen just after crossing the border, and past

buildings bedecked in fairy lights ready for Pakistani Independence Day on the

14th August. We also passed a large building which used to be the Governor's

residence in the days of the Raj (but is now a library), as well as Atchison

College (Pakistan's most famous and exclusive school, which Imran Khan

attended) and the law courts which were a fine example of the Anglo-Indian

architectural style.

Having arrived back at the hotel, I said goodbye to Mudassir, and thanked him

for his hospitality, which had made for a memorable end to my visit to Lahore. I

was extremely glad that I had been able to visit him; one of the problems of

travelling so far from home is that often you know that you will never see the

people you meet again. It was nice to defy the usual run of things.

Day 39 - Sunday 11th August.

It was time to move on once again, and I checked out of my hotel at 5 a.m. and

took a rickshaw to the railway station. I found that I only had to wait a few

minutes on the platform before the train arrived and I found my seat in the first

class carriage. Travelling first class in India had been a nightmare, because the

overhead racks were too small to accommodate my seventy-five litre backpack,

and I had to wedge it between my legs and the seat in front. Pakistani first class

carriages could not have been more different, there was acres of leg room and I

could sit comfortably even with my pack in front of me.

Soon after leaving Lahore, an attendant passed down the carriage with

breakfast trays of bread and fried eggs efficiently stacked one on top of the

other, and I bought one for Rs 20. By the time I had finished eating, we were

travelling quickly through flat green fields of wheat and maize, passing small

houses made of baked mud, concrete or occasionally of thin baked mud bricks.

Very often the little villages had a small mosque which was a larger version of

the houses but had a line of two or three small minarets at the front. I had seen

these before in Pakistan and, since the minarets were always similar, was

wondering whether or not they were mass produced somewhere. Amazingly, a

few minutes later we passed a yard where the pre-constructed minarets were

lined up ready to be transported to the various villages. Presumably each

community saved the money to build the basic structure of the mosque and

then bought one of these miniature facades to top it off.

When we stopped at one of the larger towns, one of the people joining the train

sat down next to me. He soon told me that he had recently returned from Saudi

Arabia where he had been serving with the Pakistani Army and had worked with

the U.S. Marines. He had been there during the Gulf War and had experienced

an Iraqi Scud missile attack first hand. Another attendant soon passed down the

train, this time selling sweets, and I couldn't pass up the opportunity to buy a

Jubilee bar. These chocolate bars were given to us occasionally on our 1994

trek, as a treat, and were probably the only thing that gave me the energy to

carry on on more than one occasion.

After I arrived Multan, I checked in to the United Hotel, and went for an

excellent meal at a Chinese restaurant called the Shangri-La snack house. I then

went to the Pakistsan Tourist Development Corporation and bought a T-shirt but

unfortunately it was way too big.

Back at the hotel, I was resting when a man walked right into my room through

the bathroom, the staff had neglected to tell me it was a shared bathroom – all

my things could have been stolen! There was also no way to lock the bathroom

door from my side. I had to go down to the reception and ask to be given

another room, but in this one the main door lock was hanging off. I attempted a

DIY repair job using my Swiss Army knife but to no avail. In the end I decided to

move to the Hotel Marra at Rs150 a night. This place was much better, and even

had its own restaurant.

It was hard to believe just how hot it was in Multan. At 9 p.m. in my hotel room

I measured the temperature at 36.1 degrees C!

Day 40 – Monday 12th August - Currently unfinished (notes only)

Got up early, took a rickshaw up to the Quasim Bagh + fort, walked around,

went up to the lookout point, took photographs.

First visited the Shrine of Rukn-i-Alam, incense inside, devotees touching the

cloth of the tomb to their heads, carved wood, beautiful blue tiles on the

outside. Next went to the shrine of Bahudi-Ud-Zacharia – beautiful tiled tombs

and burning incense, orginal wooden ceiling with painted designs.

Went back to hotel – 1.5 hour wait for two drumsticks in pool of oil. Went for a

proper meal at the Shangri-La – drank 4 cups of coffee and just under 3 pints of

mineral water.

Walked back to hotel, then walked round the fort most of the way to the Shrine

of Shams Tabrez (got rickshaw for last bit), fairly plain inside but fantastic tile

work on the outside. Get rickshaw back to hotel.

More itinerary changing, will probably now go quickly to Bahawalpur / Uch and

then Peshawar to Swat and Chitral.

Day 41 – Tuesday 13th August - Currently unfinished (notes only)

At 9:30 went to Multan Cantt Station, got ticket for Shalimar Express at 11:00 in

Economy, very very crowded. Scenery is green irrigated fields and sun baked

houses, see bee eaters and Indian Rollers, palm trees. Farzad Ali buys me a

drink, he is a traveling salesman selling melamine plastic items - gives me a gift

of a bowl and a photo frame.

Arrive in Bahawalpur – get ticket for Peshawar on the 15th August, go to Erum

hotel, go to the Panda Chinese restaurant for meal and 3 pints of mineral water,

came back to hotel, sleep, go out to get can of Pepsi, meet Javed Mahmood

Malik, takes me on a short tour of Bahawalpur in car – shopping complex –

medical colony (to pick up his friend Wasim and his brothers wife) drop them

off, go out to the outskirts. Go to have tea with his friends who all speak very

good English (MAs in English Lit). Get a lift back to the hotel on a motorbike.

Day 42 – Wednesday 14th August (Pakistan Independence Day) - Currently

unfinished (notes only)

Got up early, got rickshaw to Eidgah, drove all around the place before

eventually finding out that it is basically next to my hotel, got in a bus bound

for Ahmadpur East, slept most of the way (journey 1 hour). At Ahmadpur East

changed to a very crowded wagon for Uch Sharif, scenery is cultivated fields,

sun baked houses, palm trees. See a few Indian Rollers and a Hoopoe!

Arrive in the bustling bazaar of Uch, (independence Day celebrations taking

place, big crowd of school children shouting Pakistan Zindabad!), walked

through the bazaar for a bit, soon became clear that I would need a local guide

to find the tombs. Ask at a shop, given a seat and a free Pepsi, ask directions, a

bit further on find a local kid who guides me around, its difficult to make out

the names of some of the tiled tombs but the most important ones are

recognizable, firstly the Mosque and Shrine of Jalaluddin Bukhari, with its

ancient painted ceiling supported by carved wooden pillars and the footprint of

Imam Ali. The highlight was next, the spectacular ruined tomb of Bibi Jawindi

overlooking palm trees. Next to this was the shrine and mosque of Jalaluddin

Surkh Bukhari, again with a very old painted ceiling and a pool outside which

reflected the tiles.

Got back to Bahawalpur at 12:30 (we thought we had a puncture at one point)

went to hotel then to the Panda restaurant for hot sauce c hicken and 3 pints of

mineral water (due to the heat). Go back to hotel, sleep, go out for Pepsi, at 7

decide to go to Farid Gate to see the Independence celebrations (if any) streets

are full of people blowing party horns, on the way met a local English teacher,

meet up at Farid Gate have mango milkshake, motorbike ride part way to house

but all roads blocked so we walk the rest of the way, have tea. Train to

Peshawar will be 20 hours! His father is the manager of the United bank so no

problems changing TCs. His cousin works in the railway office so he says he

might be able to upgrade my ticket to a berth for the long journey. Motorcycle

ride back to the hotel.

Day 43 – Thursday 15th August - Currently unfinished (notes only)

Meet Tasneem at 09:30, go to bank but they cannot change TCs as must wait to

get the exchange rate from Karachi, go to Tasneems English school met some of

his pupils, went to his house, had tea and potatoes. Then we went back to the

school to meet some of the female pupils, talked to Uzma and Shamillah. Some

more of his male pupils arrived – go for tea in town by motorbike. V. immature

and dangerous on motorbike, eventually we have a puncture. At 19:30 got a lift

back to Tasneems house to get the backpack and camera then another pupils

dad gives me a lift to his shop where another man drives me (motorbike) to the

station.

On board train – commotion over bag. Repairs to train in desert outside Multan.

Day 44 - Friday 16th August.

By the early morning the train had reached Lahore and after a short stop we set

off again towards Rawalpindi where I had landed for my first visit to Pakistan

two years before. On the way we crossed the Jhelum, one of the five rivers of

the Punjab. On the bank of one river that we crossed I saw a man with a fishing

rod and on the end of the line, lying on the bank was some sort of green turtle.

After this the train passed through a strange landscape of small red coloured

hills which looked like a miniature version of the Grand Canyon or a copy of the

surface of Mars. The sky was dark and overcast and the resulting gloom added

to the strange scene.

After a long stop in Rawalpindi we left the city suburbs and I could see the

white shape of the Shah Faisal Mosque at Islamabad in the distance and for the

first time, my journey overlapped the one that I had made in Pakistan in 1994.

At this point a lady sitting opposite me introduced herself. Luzerat asked me

about my journey and invited me to stay at her home in Jhelum, but I explained

that unfortunately I would not be able to return to the east of the country after

my visit to the Swat valley and Chitral. As we approached the town of Attock

where she was to get off the train, she very kindly explained to a young man in

the carriage that I wanted to photograph the famous fort at Attock built by

Akbar the Great (which I knew would probably be visible from the train) and she

asked him to tell me which window to stand at and when to ready my camera

for a good view. In 1994 we had crossed the road bridge at Attock which runs

just beside the fort and the view had been spectacular but unfortunately I could

not get a photograph. This time, thanks to my guide I did manage to photograph

the fort although it was much further away from the railway than it had been

from the road and the view was not quite so good.

After we crossed the river we entered the legendary North West Frontier

Province (NWFP), home of the Khyber Pass and the tribal lands of the fierce

Pathans. A few seconds later, as I was thinking how peaceful the countryside

looked given the violent history of the province, a loud rattling noise suddenly

erupted from the vicinity of a group of houses. At first I thought it had been a

noisy rickshaw exhaust but then I suddenly realised exactly what had caused it.

To confirm my speculation the man who had helped me take the photograph

mimed the action of someone squeezing a trigger. "Kalashnikov", he said simply.

The rattling noise had been a burst of automatic fire from an AK-47, no doubt

one of the locals showing off to his friends. The fact that it had taken all of a

few seconds since entering the NWFP for me to hear gunfire reminded me that I

had started the most dangerous phase of my journey.

The train rattled on, through the low khaki hills, before running parallel to the

Grand Trunk Road as we neared Peshawar. I arrived at Peshawar railway station

at 6.45 p.m. having been on the train for about twenty hours. I was absolutely

filthy and desperately tired but fortunately I soon got a room at Khani's Hotel in

Sadaar Bazaar where I was able to clean myself up.

Day 45 - Saturday 17th August.

I left early, eager to get up into the cooler climate of the Swat valley after the

extreme heat of the southern Punjab and Peshawar. For the first stage of the

journey I took a rickshaw to the General Bus Stand where I boarded a wagon

that was heading for the twin towns of Saidu Sharif and Mingora, which have

merged to become one town. We headed east down the Grand Trunk Road and

then north through the small town of Takht-i-Bhai; where a small group of men

were loading large bails of dried tobacco leaves onto waiting trucks. From there

the road climbed sharply up into green bush covered mountains to a height of

about three thousand feet allowing spectacular views of the Vale of Peshawar.

At the top of the climb we crossed the Malakand Pass and gradually descended

into the lower Swat valley. Even from that point it was still a fairly long drive to

Mingora, and the road passed through an area which contained many important

Ghandaran Bhuddist sites. We saw one site, the large Shingerdar Stupa, from

the wagon as we drove past. It was a large dome of red-brown bricks with many

shrubs sprouting from the top. The river and the valley itself were only

occasionally visible through the trees but they were an impressive sight. At this

point the river had spread out across the valley in a great grey sheen; the

colour was caused by the large amount of sediment carried down from the

mountains in the water.

At the bustling and congested town of Mingora I changed wagons, climbing on

board one that was heading for the tiny town of Madyan, much further up the

valley. As we drove higher up the valley side the scenery became more and

more dramatic and by the time we had arrived in Madyan, my final destination

for the day at about 4000 ft, the air had become cooler.

The wagon dropped me in the middle of a very small bazaar and I carried my

pack a short distance to the north, along the muddy street and over a bridge to

the Nisar Hotel.

After a brief rest I set off with my camera to walk up the Madyan Khwar, to a

meadow area called Chil. The Madyan Khwar is a side valley that runs east out

of the little town (the bridge that I had crossed on the way into town spanned

the river emerging from it). My guide book claimed that the walk took only a

few hours and was safe. Initially I found it difficult to find the start of the small

path up the south side of the valley, but eventually I realised that it began in a

dingy alley leading out of the bazaar. This soon emerged onto a wide stony track

and I found myself walking with a Pakistan Fisheries worker who told me that I

was going in the right direction and, as we climbed further up, he pointed out

the trout farms where he worked that were down by the riverside. Close by was