Rowan Castle - Travel & Photography

© Rowan Castle 2019

Venezuela 2000 - Diary

Day One - Friday 1st September 2000.

The ‘Expedition to Angel Falls’ got off to a rushed and stressful start when the

Alitalia flight from London was delayed by an air traffic control problem. This

meant that when I landed in Milan (after a breathtaking flight over the Alps), I

had just twenty minutes until my connecting plane to Caracas was due to

takeoff! It might have been less of a problem if we had docked at a gate, but

instead we stopped in the middle of the apron and had to board buses for the

terminal. The difficulty I faced was that Geodyssey specify that the expedition

starts when you are met by their representative at Caracas. In other words,

although they had sold me my flights, the responsibility for getting to Caracas

rested with me! If I had missed my connecting flight it would have been

unlikely that I could have got on another one in time to meet up with the

others in Caracas, and for me, the expedition would have been over before it

had started. I made it with just ten minutes to spare.

Once on board the 767 for Caracas I could at last relax and enjoy the flight, as

we cruised past the impressive Mont Blanc range, over France, Northern Spain,

Lisbon and then out across the Atlantic. Once we had made good progress over

the ocean, I asked one of the flight attendants if I might be able to go up onto

the flight deck to meet the pilots. An hour later, I was escorted up to the

cockpit, and invited to sit in the third seat for a while. It was the first time I

had been on the flight deck of a large airliner and I had a spectacular view

across the cloudscapes. The captain pointed out a small thunderstorm system

to our right and then showed me the corresponding angry red blob on the

weather radar return. They asked me why I was going to Venezuela, and I

briefly described where I would be trekking. At this point we must have got our

linguistic wires crossed briefly, the captain had asked me if I 'dealt in four

wheel drive' and I thought he was asking if we would be using the vehicles on

our trip. When I said yes, he asked me if I knew of anywhere he could buy re-

conditioned door panels for his Land Rover!

The remainder of the ten hour flight passed uneventfully, and we didn't see any

land until we flew over the Dominican Republic and other islands in the

Caribbean. I watched the moving map display on the monitors as we got

steadily closer to Caracas and the 'Kilometres to go' count slowly ticked

towards zero. Suddenly we sighted the South American coastline, the forested

shoreline rising quickly to form the Avilla Mountains. This small range lies

between Caracas and the sea. Throttling back, we soon touched down at the

International airport, which is on the coast at Maiquetia. I had arrived on a new

continent.

I was met in the Arrivals hall by Senora Chris Crepsinek, who had her own tour

company, but had been sub-contracted by Geodyssey to meet me (and later on

that evening, Richard) at the airport and take us on the eighteen kilometre

drive through the Avilla Mountains into Caracas. As we emerged from the

International terminal, I was surprised to find that it was not that hot outside,

just 22 degrees C. The first thing that I had noticed about Venezuela was the

extraordinary colour of the soil - a rich orange brown, although this soon

disappeared beneath the green of the heavily forested slopes of the mountains

above us.

The road to Caracas rose steeply from the shore and up into the mountains.

The dual carriageway was busy, and in places we ground to a halt with the

congestion. I was informed that the typical journey time to travel the eighteen

kilometres was about an hour! We passed through several very long and

impressive road tunnels, which cut through the heart of the mountains and

allowed us to emerge into the Caracas valley, about four thousand feet above

sea level. The hills at this point were smothered in the ramshackle shanty

towns (ranchos) of Caracas, which extended as far as the eye could see. From

here we weaved our way through the frenetic traffic of big old American cars

and landcruisers; most of which had completely bald tyres.

Soon we were in the heart of modern Caracas, the glass fronted skyscrapers we

passed a testament to the oil money that had been lavished on the capital.

This was a city that definitely favoured the car over the pedestrian, with great

sweeping flyovers and expressways. There were however some very beautiful

parks along the roadside, filled with interesting trees. I was enjoying the drive

through the great, sprawling metropolis and it seemed a shame that I would

only be spending one night here. It was already early evening when we pulled

up outside the Hotel Las Americanas. I was checked in, arrangements were

made for the very early start the next morning and I was shown to my room on

the first floor.

At half past seven Richard arrived at the Hotel and we had dinner in the

rooftop bar. I had spoken to Richard by telephone before leaving the UK and

knew that we would get on on the trip. He had a wicked sense of humour, and

like me, was heavily into trekking gadgets of every kind. From our vantage

point we had a good view of the whole of Caracas and the mountains around.

We were both looking forward to setting off in the morning and starting the

expedition proper. By this time it was quite late, and as we had an early start

in the morning, I went to bed.

Day Two - Saturday 2nd September.

At 05.45 a.m. we left the hotel with Chris, and she drove us back down to the

domestic airport terminal at Maiquetia. After Richard and I had had a hurried

breakfast in the departure lounge we boarded a DC-9 bound for Ciudad Guyana

(Puerto Ordaz), on the Orinoco River. On take-off, we flew over the sea but

parallel with the shore before turning inland and heading south. The terrain

below was obscured by cloud, and it wasn't until we began our descent that we

saw the massive Orinoco River below us, and the roofs of the houses of Puerto

Ordaz. As we landed I saw several old DC-3 airliners parked by the terminal.

These twin engine propeller driven aircraft were built prior to world war two

and are still used by Servivensa (one of Venezuela's domestic carriers). We were

originally booked to fly with that airline, and would probably have flown back

after the trek in one of the DC-3s. It was a shame that we eventually travelled

with the Avensa airline, and didn't get the chance to fly in one of these historic

and charismatic aircraft. The DC-3s were accompanied on the tarmac by several

interesting float planes, no doubt these were used for landing on remote lakes

or perhaps even stretches of the Orinoco River.

As we entered the airport terminal we were met by our expedition guide,

Ricardo Brassington. It transpired that Ricardo was mainly a freelance guide

who had been leading group expeditions in Venezuela for sixteen years. He

would be the trek leader once we entered the jungle. Accompanying him was

Billy Esser, a second guide who usually ran a popular guest house and chocolate

plantation on Venezuela's Caribbean coast. His role in the expedition was mainly

to assist Ricardo with organising the logistics and also to drive us south to the

Pemon Indian village where our trek would begin. Richard and I were next

introduced to the third participant in the expedition, Janet Ludlow. Janet was

retired, and lived in Venezuela for six months of the year in a log cabin near

Billy's guest house. As a result she was a friend both of Billy and Geoddysey and

had been persuaded to join the trek at the last minute to boost the numbers

and lower the costs. Stepping out of the terminal, we were lead to a smart

Toyota Landcruiser 4WD, where we met the final member of the expedition

team, Johan. He was a relative of Billy's from the Andean province of Merida.

He had been holidaying with Billy at the guesthouse and had come along to see

a new part of his own country. It was to be a great journey for him. He was only

fifteen years old, and very few children of his own age in Merida would have

travelled as widely as him by the end of the trip.

We sped off in the Landcruiser, and Ricardo informed us that because Janet had

joined the trip at the last minute, they needed to go into town to buy her some

equipment and also to get some camping gas canisters for the expedition. To

save Richard and I from traipsing around the shops, we were dropped off at

Cachamay park, by a dramatic line of rapids and waterfalls on the Caroni river.

At the far end of the park was a miniature zoo garden, which housed some of

the wildlife rescued when land was flooded during the construction of a hydro-

electric dam. Richard and I didn't make it to the zoo though, we were too busy

running around inside the park taking photographs of the amazing wildlife that

was all around. There were many butterflies, principally of two kinds - a red

and black species (which I later identified from a butterfly book as Anartia

amathea of the Nymphalidae family), and a brown and yellow type. We also saw

a huge rainbow coloured beetle, large ants and a herd of wild pigs. By far the

most spectacular creature to be seen (and something that I had really hoped to

see on the trip) was the blue morpho butterfly. This stunning insect is almost as

big as your hand and electric blue in colour. Instead of flapping its broad wings,

it glides majestically through the trees, flashing in the shadows as it catches

the light. The first time I saw one I was absolutely transfixed, and then I tried

to dash after it to get a better look. Unfortunately, they are extremely fast

flyers and rarely settle. We saw many blue morphos during the trek, mainly

flying up and down rivers and streams or flitting through the sunlit forest

canopy.

Cachamay Park, Puerto Ordaz, Venezuela.

We emerged from the park at the time we were due to be collected in the

Landcruiser, but the others were late. Richard and I waited in the car park at

the side of the road. It was much hotter here than in Caracas and the humidity

made it an uncomfortable wait. The rest of the group arrived at about eleven

and we set off south down the highway. By nightfall we would be in the

Canaima National Park which encompasses the plateau area known as La Gran

Sabana. It is this area that is dotted with the huge table-top mountains and is

where Angel Falls plummets into the rainforest from the top of Auyantepui

(which means 'Mountain of the God of Evil').

The highway that took us south was metalled and well maintained. It runs from

Puerto Ordaz on the Orinoco river right down to the town of Santa Elena de

Uairen on the Venezuela/Brazil border and then on into Brazil itself. Once out

of the suburbs of Puerto Ordaz, the first large town that we passed was Upata,

named after a beautiful maiden who had been forced into marriage and then

killed herself. We stopped there at a large roadside garage so that Billy could

buy a new jack. He explained that the one that had come with the Landcruiser

was inadequate for use on the rough roads that we would have to navigate on

the way to the start of the trek.

Our next stop was at a dusty shop near the tiny settlement of Cintillo. The shop

specialised in making a cheese called Telita that was a staple of the region.

Ricardo ordered a plate of it for us to try. A huge white, wobbling square of

cheese was then produced and cut into slices. The taste was very salty but

quite pleasant. We were then treated to some soft, crumbly gingerbread which

was delicious, and Ricardo bought a large hunk of it to be taken with us on the

trek. Resuming our journey it was then only a short distance to the village of

Guasipati, which in the indigenous language means 'beautiful land'. It was a

fitting name; the road ran past little houses with raised gardens of flowers, and

the people we passed waved and smiled at us. This highway seemed to be

typical of the way that the interior of South America had been developed. After

the highway had been constructed, these little houses and ranches had been

built on cleared strips of land next to the road, so that people and communities

were strung out along its length. The beauty hid the fact that after the bush or

forest is cleared and grazed, it often loses its fertility and can become useless.

This is the cause of much deforestation. However, running parallel to the road

and often visible, was an even worse cause of forest clearance. The Venezuelan

government had decided to sell its surplus hydro-electricity to the Brazilians.

They had constructed a line of pylons and cables running parallel to the

highway and extending all the way to the border and out into Brazil. This had

meant that a large swathe of scrub and rainforest had been cleared for

hundreds of miles, cutting right through the territory of the indigenous Indians.

Our next stop was in the small gold mining town of El Callao (pronounced El

CAI-oh), where Papillon (a famous French gangster and author) had lived briefly

on his release from the prison at El Dorado. Ricardo explained that according to

local legend, the town originally got its name from a secretive gold prospector.

Every day the prospector quietly left the other miners, and went off into the

forest on his own. After a while the other miners noticed this and nicknamed

him 'the quiet one' or 'El Callao', in Spanish. They knew that he must have found

a lucrative area for gold and one day they managed to follow him, and found

the place where the town stands today. Gold is still mined here in large

quantities, and the biggest operation is the state owned Mina Columbia - the

deepest gold mine in Venezuela.

We pulled up in the town square - Plaza Bolivar, which was surrounded on all

sides by shops selling gold jewellery. Ricardo bought some interesting fruit for

us from a street vendor. It was called Ginip, and was rather like a green lychee.

You bit into the outer hard skin, peeled the two halves apart and then sucked

on the fleshy stone. There wasn't a lot of fruit inside, I think it was a case of

more calories expended eating it than there were gained! While parked in the

square, eating Ginip, I noticed that on a nearby hill I could see where a large

swathe of trees had been cut down to make way for a gold mine. The mining

has caused a lot of devastation here, in an area that is important for

conservation. This area of rainforest is known as the Imataca corridor, because

it provides a forest 'bridge' between the great regions of the Amazon to the

South West and Guyana to the East. Wildlife is able to move between the two

via this forest corridor so it is important that it remains intact. Geodyssey are

helping with a conservation project which aims to protect this habitat for the

future.

Moving on, we came to the town of Tumeremo. It was here that we stopped for

lunch (in my case fried red snapper fish) in a small roadside restaurant. It was

run by a short Guyanese lady with gold teeth. Ricardo explained that many

Guyanese people live on this side of the border. This is because Venezuela has

laid claim to the territory of the former British Guyana and all of the Guayanese

are considered de facto Venezuelans. Incidentally, although Ricardo was

Venezuelan born, it was actually in the capital of Guyana (Georgetown) that he

grew up.

From Tumeremo, the road took us almost directly south to the slightly squalid

gold mining town of El Dorado. El Dorado is 'Kilometre 0' on the highway south

to Brazil, and many of the places we passed through from now on were referred

to by their kilometre number as well as (or instead of) the actual name. We

were due to stay on the main road, largely by-passing the town altogether, but I

had asked Ricardo if we could go into the centre to see the famous prison

where Papillon was held. So we darted off the main road and soon found

ourselves in the dusty streets of El Dorado. We pulled up at the bank of the

Caroni River, and there on an island in the middle was the penitentiary. Not a

lot was visible from this distance, mainly a large white guard tower and lighting

masts. The Caroni River is rich in diamonds, and it was while Papillon was in

prison on the island that he discovered a large diamond in some water that he

had drawn to feed his tomato plants. Ricardo told me that one of his friend's

grandfather used to play cards with Papillon when he lived in Caracas!

The Cuyuni River and Prison at El Dorado, Venezuela.

We rejoined the main road, and quickly left it again using a redundant track so

that we could cross the Caroni on an old bridge that had been built and donated

to Venezuela by the French architect Eiffel (of Eiffel Tower fame). The main

road crossed next to us on a modern concrete monstrosity, and I was glad that

we had the chance to stop on this old bridge and admire the wide river, with

dense forest on either side.

Janet on Eiffel’s Bridge, near El Dorado.

Leaving El Dorado, the road was crowded on either side by very dense, brilliant

green rainforest. The only break that we saw was when we briefly passed a

helipad with resident helicopter, one of many used to take parts and supplies to

the small gold mines that dot the region. Up ahead the sky was dark and angry

with thunder clouds, and the golden evening sunlight highlighted an enormous

Apamate tree, covered in pink blossom, which towered above the surrounding

tree line. The petals were being blown from the crown of the tree in pink

flurries, standing out against the dramatic sky behind. It was a beautiful sight,

and so the Landcruiser was stopped at the side of the road while we all piled

out to take some photographs. Very soon afterwards, the rainstorm hit us and

lightning flashed overhead. It was so heavy that the road and forest in front of

us all but disappeared in a grey-green blur. We had intended to re-fuel the

Landcruiser at El Dorado, but the only petrol station had been put out of order

by a power cut. As a result we were now running quite low on petrol and had to

turn the air conditioning off to conserve what was left. As soon as the switch

was pressed, the humidity of the forest flooded in.

Apamate tree and storm clouds.

At Kilometre 88 we reached the tiny settlement of San Isidro, where we stopped

for petrol. It was really just a run-down truck stop in the middle of the

rainforest, but very atmospheric. Two parrots raced noisily across the sky up

ahead, and although it had now stopped raining, the air was heavy with

humidity. Next to the petrol station was a large liquor store where Ricardo

bought a bottle of rum so that we could have Cuba Libres (Free Cuba - rum and

coke) later on.

The Sierra de Lema Mountains were now up ahead, and with the light failing,

we began the steep climb up the section of road known as La Escalera ('The

Stairway'), which would bring us out onto the plateau of La Gran Sabana. This

part of the road is reputed to be one of the greatest spots on the whole South

American continent for bird-watching. Part way up the climb, at Kilometre 99

we came to a massive sandstone boulder, Piedra de la Virgen, which marks the

entrance to the Canaima National Park. It is reputed that this rock resisted all

attempts to dynamite it when the road was built, and so it remained

undisturbed. From the foot of the rock we had a superb view out across the

rainforest that we had just driven through. It was dotted with small mountains

that were wreathed in cloud. The light was fading fast, but I managed to take a

photograph by supporting my camera on a mini tripod on the roof of the

landcruiser. After we had taken some photos, Billy excelled himself by

producing a can of cold beer for each of us, from a cool box in the back of the

Toyota. So we stood by the side of the road, drinking ice cold lager and looking

out across the beautiful forest - an unforgettable moment.

The view from Piedra de la Virgen.

Driving on further up the mountain, through dense jungle, Ricardo told us about

the time he had driven a family with young children past that very spot. As they

had rounded a bend in the road, a jaguar had walked slowly and calmly across

the road in front of them; a very rare event. He confirmed that there would be

jaguars in the area where we would be trekking. It was here that we came

closest to the border with Guyana, just 3 km away.

The road levelled out and we drove on through the darkness. We were now out

on the savannah. Occasionally the terrain we were passing through was briefly

illuminated by a flash of lightning, but otherwise we could see nothing outside

the range of the headlights. We came to a junction in the road, where the right

hand turn lead to the Pemon Indian village of Kavanayen, where our trek would

begin. However, we ignored the turn off and kept on the main highway south,

which would take us to Kamoiran Lodge, our accommodation for the evening.

The lodge (and petrol station) had been built by the Pemon Indians to bring in

tourist revenue, and was constructed of stone blocks using a method they had

learnt from the missionaries who had converted the Pemon to Catholicism.

On arrival at the lodge, we discovered that our rooms had been flooded by the

evening's downpour and were being mopped out. We decided to have dinner and

a round of Cuba Libres (with lime juice) while we waited. During dinner Billy

opened a bottle of very nice Chilean red wine that he had bought called

Casillero Del Diablo which means 'the devil's cellar'. After dinner we moved out

to a table under the porch for drinks, and while we were chatting I spotted a

beautiful brown frog which was perched on a plant stem next to the table. It

stayed there for most of the night, fixing us with it's big bulging eyes. While we

drank, Billy told us some stories from his sixteen years of working with Ricardo

as a jungle guide - the honeymoon couple whose DC-3 flight ended in a bad

crash (which didn't stop them going on to their beach hut on the coast) and the

jungle trekker who sprained his ankle and had to ride out on a mule because

the helicopters were busy. Most unnerving was the story of how he had tried to

open a new jungle route from Canaima to La Bonita which ended with the group

soaked to the skin, lost and eventually rescued by gold miners!

After our chat, Billy, Richard, Johan and I walked down to the Kamoiran

waterfall (which was just at the end of the grounds of the lodge) by torch light

and found a big freshwater crab. Richard and I agreed to meet at the waterfall

at first light (5.30 am) to take a dip.

Exhausted after the long day's travelling, I went to my room and collapsed on

the bed. After I switched the light off, I was amazed to find that there was a

firefly in the room! I could see the bright green light it produced flashing on and

off as it climbed the wall in front of me. I switched the light back on and went

to examine it more closely. It was then that I could see it had become trapped

in a spider’s web, so I rescued it with the end of a candle and it went on its

way.

Not all of the insects in the room were as pretty or as welcome as the firefly. I

could frequently hear the tell-tale whine of tiny mosquitoes in my ear, and

occasionally in the night I was woken by the sound of a truly giant insect

crashing and bouncing off the corrugated iron roof and hitting the walls.

Day Three - Sunday 3rd September.

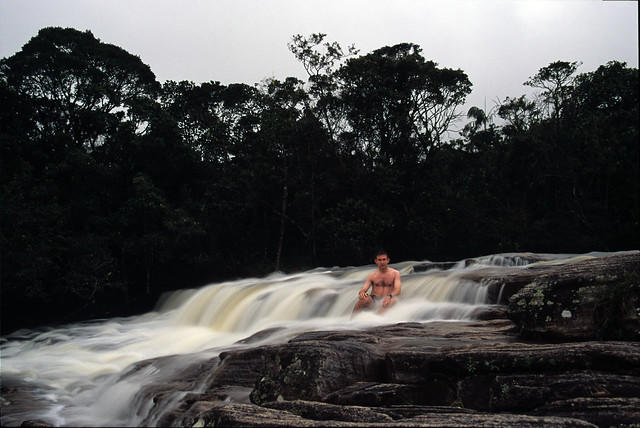

True to our word, Richard and I were down at the waterfall by first light. The

shallow falls were beautiful, and I set up my camera and mini tripod to take

some photographs. After that I sat in the freezing torrent of water, which is

definitely the most refreshing way to wake up. Ricardo also joined us for a dip;

we washed our hair and then headed back to the lodge for breakfast of eggs

and bacon.

Me, in the waterfall near Kamoiran Lodge.

At 7.30 we set off in the Landcruiser back up the highway to the turning for

Kavanayen. The road lead roughly west, and was an unmetalled but fairly level

track across the rolling grassland of the savannah. Occasionally it was eroded or

rutted quite badly and Billy had to select four wheel drive. In places there were

patches of bare soil by the roadside that were in bands of extraordinary colours

- pinks, reds, oranges and shades of brown. Areas of the soil and rock had

sometimes been weathered into tiny versions of the tepuis. The grassland was

dotted with large termite nests and Ricardo said that we might be lucky and see

a South American ant eater foraging across the plain, raiding the mounds as it

went. We passed a surprisingly long tarmac runway that was built by the

military. This was the remote airfield of Luepa; it is usually used by F-16 fighter

jets of the Venezuelan Air Force, but was once used by a Boeing 747 airliner for

an emergency landing! Next we drove through a place called Perupa, where

some scientists were conducting plant experiments, chief of which was the

planting of pine trees. There was nothing to see except the small stands of

trees themselves. Ricardo was against this idea, mainly because of the danger

that the alien pines would be too well suited and take over the savannah.

We stopped at a large Pemon thatched hut (known as a churuata), and a sign

outside pronounced that it was a 'mini panaderia' - a bakery. Remarkably, inside

this hut in the middle of nowhere were expertly made cakes and buns, neatly

laid out on a counter. We had a snack of buns and coffee, while the Pemon lady

in charge went off to capture her favourite pet to show us, a beautiful baby

fallow deer. As soon as she put it down on the ground in front of us it charged

off across the savannah at a rate of knots and disappeared from view. As we ate

there was a brief but heavy rain shower and the sky was completely overcast.

The terrain ahead was severe, but Billy's expert use of the four wheel drive

brought us to the top of a rise, where there was an unfinished stone building.

From here we could see our first proper tepui - known locally as the Sleeping

Indian. By now we were very close to Kavanayen and a steep descent through a

muddy forest brought us into the village. Kavanayen is set in the middle of wide

savannah, ringed by tepuis. We found ourselves among tidy stone built houses

(made in the same way as Kamoiran lodge) interspersed with palms. The Pemon

were friendly, and waved or smiled as we passed by each doorway. We pulled up

outside the very large Catholic mission, which is usually open to visitors.

Unfortunately, it seemed that they had had some undesirable visitors of late

and the priest had decided to lock the building until further notice. Ricardo had

gone somewhere in the village to find Bruno Lambos, a Pemon Indian who would

be our jungle guide and head porter. While we waited, the heavens opened and

the water streamed off the mission roof, splashing noisily from overflowing oil

drums.

There was a public telephone in the entrance way of the mission, and Johan

was busy trying to contact his family in the Andes. He wanted to ask his

mother's permission to join our expedition into the jungle and on to Angel Falls.

Originally, it had been planned that he would only accompany us as far as the

Karuai waterfall, our trail head, and then drive back with Billy. However, after

checking that it would be OK with Richard and I, Ricardo and Billy had agreed

that he could come along, on two conditions. The first was that he worked as a

porter, carrying most of Janet's equipment and the second was that his mother

gave him permission, since the trek we were about to undertake was potentially

hazardous. I was amazed that Richard and I were even consulted, as I thought

that it was a good idea that Johan come along for the journey of a lifetime, and

didn't consider that I had the right to exclude him. Janet explained that we had

been asked because some paying travellers get quite annoyed about unexpected

non-paying guests. It's difficult to believe how people can be so unreasonable.

Johan couldn't get through to ask his family, so luckily Billy chose to ignore the

second of the conditions he had set and allowed him to come along anyway!

We were lead to a house to kill some time until Bruno arrived, apparently he

was on his way back to the village and wouldn't be long. In front of us was a

kind of counter, on which various Pemon handicrafts had been laid out. These

were largely ornamental but genuine reproductions of articles the Pemon

actually used - longbows, hammocks, bracelets, and slender blowpipes with

quivers of darts. Also on display was an item we commonly saw throughout the

trek - a cassava squeezer. This is essentially a long tube made of a mesh of

strong palm fronds with a round handle on each end. Cassava (manioc) is a

staple of the Indian diet and is a root vegetable. Unfortunately, the juice inside

the root is extremely poisonous (containing cyanide). The mesh tube is used to

squeeze the cassava dry, until it resembles mashed potato and is safe to eat.

There are two types of cassava, a sweet variety containing little poison (which

can be eaten fresh) and the bitter variety (grown by the Pemon) which must be

processed in order to avoid cyanide poisoning. The bitter variety is favoured as

a crop because it is more drought resistant and will grow in poor soils. Ricardo

showed us how to easily identify the bitter variety - the central leaf of each

plant is purple whilst the others are green in colour. Next to the cassava

squeezer was a large polystyrene block with the outline of a cock-of-the-rock

bird drawn on it. This was used to allow prospective blowpipe purchasers the

chance to practice their aim, and by the time Ricardo returned from his

wanderings, Richard and I were quite good shots - as long as we were only four

feet away! The darts were an incredibly snug fit in the barrel of the blowpipe,

and it didn't take much effort to imbed the sharp tip in the polystyrene with

some force.

Just then Ricardo reappeared with Bruno, who would be our guide for the next

six days. Like most of the Pemon Indians, Bruno was short in stature, with jet

black hair and a weathered face. He was dressed as he would be for our entire

trek - in a pair of white wellington boots, battered trousers, a long shirt and a

very worn 'Houston Rockets' baseball cap.

We walked as a group to the other side of the village and had lunch in a

restaurant. The food was very good, consisting of chicken, rice and sweet

banana, washed down with Coca Cola. After lunch, Janet, Richard, Billy and I

relaxed outside while the final preparations were made for the trek. Billy had

brought some chocolate from his plantation for us to try. We had chocolate

drops that consisted of 85% cocoa solids (as compared with the 10-15% content

of British chocolate). The taste was sensational and the chocolate was so strong

you could actually feel it rushing to your head! He also produced another cold

beer for each of us from the coolbox in the back of the Toyota, but at the same

time discovered it had leaked and soaked all of Janet's spare clothes. She

quickly rigged up a washing line and hung them out to dry.

All of our baggage was then re-arranged in the back of the Landcruiser in order

that we could accommodate Bruno for the drive to our trailhead at the Karuai

Waterfall. Our other three porters, Juan, Alejandro and David (Bruno's

Grandson), had already set off on foot to the waterfall, and would meet us

there. One other vital safeguard had also been taken; Billy had used the radio

transmitter at Kavanayen to inform his contacts at Kamarata (the Pemon village

at the end of our trek) that we were about to set off and would be with them in

six days. If we hadn't emerged from the rainforest by then, a search would be

mounted.

At last we set off for Karuai, along a very rutted and bumpy jeep track across

the savannah. Johan had had to ride in the back of the Toyota, almost buried by

our luggage. As we bumped and lurched along the rocky trail, we disturbed

large brown lizards that were basking in the sun or startled Crested Caracara

hawks into the air. The plain was covered in scrub vegetation, mostly small

trees and green bushes. Occasionally we saw beautiful white orchids with

bulbous flowers, and yellow flycatchers darted from tree to tree. We glimpsed

an impressive line of tepuis on the horizon, and I asked if we could stop to take

some photographs. Bruno knew of a good lookout point just ahead, and after

about another quarter of a mile, we stopped at the foot of a hillock and

climbed on foot. The terrain was rough and we had to weave through the

vegetation, including strange sponge like mosses that clung to the ground and

rocks. It was wise to be careful where you put your feet, because Ricardo had

warned that there were rattlesnakes in this area. We reached the top and found

ourselves looking down a shear escarpment onto the forest below. On the

horizon were the dramatic forms of the tepuis, like a row of irregular teeth.

Rejoining the Toyota we continued our drive. The track was extremely rough by

this point, and Billy had to concentrate on where exactly to put the wheels, as

well as using the four wheel drive in the 'low' setting in many places. Shortly

after overtaking Juan, Alejandro and David, we arrived at the grassy bank of the

Karuai River, next to a large Churuata. We had passed a few small Pemon

houses, and Ricardo informed us that this was the settlement of Karuai, of

which Bruno was the Cacique (Chief). While we waited for the other porters to

arrive, Ricardo suggested that we made the short walk upstream to see the

Karuai waterfall. The trail lead us through a copse of rainforest alongside the

river bank. At one point we found a ragged line of leaf cutter ants, all carrying

carefully sized leaf pieces back to their nest. We had to cross a narrow stream

via a high log, where I slipped and nearly fell off. After a short distance the

path emerged onto large boulders at the edge of the river, about 200 metres

away from the spectacular falls.

Karuai Falls, Gran Sabana, Venezuela.

Returning to Karuai, we found that the other porters had arrived and all our

equipment had already been unloaded from the Toyota. Everyone pitched in to

help shuttle the equipment downstream along the riverbank, to the dugout

canoe which would take us down river to our first camp. The gear was carefully

loaded aboard and then covered with a black tarpaulin, in case of rain. We said

goodbye and thank you to Billy, who was waiting on the bank. His job was now

finished, and he faced a long journey back to his posada on the Rio Caribe,

Paria. We shoved off into the middle of the river, and the outboard motor

spluttered into life - this was it, the expedition to Angel Falls had begun.

Our dugout made rapid progress down river, while we just relaxed and watched

the dense rainforest slip past on either side. From time to time there were

sandy shores or sandbanks just below the water and then the outboard was

idled, and lifted as we glided over. The sand was a golden brown, and the river

water itself was dark from the tanins excreted by the decaying leaves. The

rivers in this area are rich in gold and diamonds, and Bruno had even brought a

set of sieves with him so that he could search for diamonds during the trek.

As we motored along, we saw two Toucans fly overhead and disappear into the

forest canopy. The noise from our boat often disturbed large Amazon

Kingfishers, which raced downstream with an undulating flight to settle on

another branch, only to flee again as we got closer. Sometimes they would

stand their ground for a while, squawking noisily with their hackles raised. As

our river journey progressed, we were mostly hemmed in on both sides by

dense forest, but sometimes open savannah appeared to our right and on one

such occasion we saw Ptari Tepui bathed in the late afternoon sunlight. After

about forty five minutes we moored at a rock bar projecting from the right

hand bank. This was as far as we would be going in the dugout; just beyond the

bar the current quickened and not far ahead, plunged over Salto Hueso (Bone

Waterfall). The falls had got their name because human bones had been

discovered at the bottom. The falls could not be seen from the bar and so

presumably in earlier times people had carried on and been swept to their

deaths. We each took our own equipment, and made our way carefully off the

slippery rock and along a trail through shoulder high grass. From here we could

see the falls, and it became apparent why they would have been so dangerous.

The water sped down a smooth, steep bank of rock which stretched the width

of the river, and then crashed into massive boulders at the bottom. It would

have been like racing down a log flume into a brick wall. After the falls, the

river widened and was bisected by a small island. More large boulders were

scattered here and there, and at the bank that we were on, the water lapped

at a flat sandy beach. In a grassy clearing above the shore was our camp for the

night, a permanent corrugated iron hut that belonged to Bruno's family. Behind

the hut was a backdrop of dense forest, but the immediate area had been

cleared by the Pemon to cultivate cassava. It was the rear part of the hut that

had been allocated for us to sleep in, which meant that whenever we entered,

left or moved around by the hut we had to be careful about standing on the

'garden'. What looked like ordinary bushes were actually carefully tended crops.

We dropped our equipment at the hut, and went straight down to the sandy

beach for a swim. The water was quite cold, and I had to be careful of the

sharp rocks that were submerged just below the surface, but the swim was very

refreshing.

Once we were back at the hut, darkness fell quickly. We got out our head

torches, Richard unfurled his foam sleeping mat and we sat on the earth floor

of the hut drinking rum and coke. Gradually, the winking green lights of fireflies

appeared, until there were a multitude of them stretching away into the forest;

a beautiful and atmospheric sight. The scene became even more magical as

lightning flashed overhead.

Ricardo had been cooking during all of this and served up a delicious chicken

dinner, while Richard very kindly opened a bottle of wine he had bought in the

liquor store at San Isidro and shared it around.

After the meal, I was watching the fireflies when I suddenly had a bizarre idea.

It occurred to me that the chemicals in the green snaplights I had in my

rucksack were the same ones that the flies produced inside their bodies to

generate the light we could see. I took a plastic snaplight out of my rucksack

and bent it until the glass phial within cracked open and it radiated a bright

green chemical light. Then I started waving it in periodic flashes at the fireflies

out in the forest, holding it behind my back in between the 'displays'. Sure

enough, the insects thought that I was a giant firefly and started a fantastic

display of flashing green lights. Not only did more flies appear, but they came in

closer to the camp and a few even flew through the air while their little light

was switched on. It was an amazing experience.

By then it was time to turn in for the night, and my first attempt at sleeping in

a hammock. Getting in was definitely the worst part, but once safely inside I

found it quite comfortable and relaxing. The unfamiliar sounds of the forest

kept me awake for a while, until fatigue took over and I slept soundly.

Day 4 - Monday 4th September.

In the early hours of the morning I had to get up to go to the toilet, and

swivelled carefully out of my hammock and into the all-terrain sandals that I

wore in camp. I tried unsuccessfully to duck under Johan's hammock to reach

my backpack and ended up crashing into him. It was earily silent as I made my

way out of the hut and towards the latrine that Bruno had dug the day before.

When I switched my head torch on I was amazed to see that the air was a soup

of strange particles, drifting on the breeze. I still don't know what they were,

perhaps a mixture of insects, seeds and spores, but it reminded me of an

undersea view of plankton moving with the tide. Once back in my hammock, I

had trouble getting to sleep again, especially when I heard a distant throaty

roar from the forest. At the time I thought it was a Jaguar, but when I described

it to Ricardo and Bruno the next day they thought it was more likely to have

been a howler monkey.

I wanted to take some photographs of Salto Hueso at dawn, and so I was up at 5

a.m. before it was light and made my way down to the sandy beach. I then

moved upstream by the light of my headtorch over the jumble of rocks at the

foot of the waterfall. Wanting to get even closer, I leapt onto a large boulder

and started to look for good angles to photograph from, when it got light.

Suddenly, I saw a dark shape flying through the air to my right. Initially I

thought it was a large moth but then realised, to my horror, that I had disturbed

a small colony of bats that were living in a crack in the rock. About ten of them

were now circling silently round my head. Normally I'm not too worried about

bats, in fact at home I sometimes throw bits of twig or small pebbles into the

air to watch them give chase with their 'sonar'. Out there in South America

though, where there are vampire bats, it was a different story and I beat a

hasty retreat; returning to take the photos when it got light.

At dawn, Richard joined me and we went for a swim. I washed my hair, had a

shave and then returned to the hut for breakfast of eggs and bacon. Amazingly,

Richard had brought a glass bottle of barbecue sauce from a supermarket at

home, and we all had some with our breakfast. The bottle actually survived

intact for the entire trek. To top off breakfast, we had delicious passion fruits

and mangoes to eat. As we readied our packs to begin the actual trek, I was

given a wooden bowl full of the Pemon alcoholic fermented drink to try. It was

bright pink in colour, and is made from bitter cassava (the poisonous kind) and

sweet potato. It didn't actually taste too bad, and is said to give you strength.

We learnt that Bruno's family had also decided to make the journey to

Kamarata, although they would walk ahead of us and camp at different places,

so that we could all be accommodated on the trail.

Me, waiting to start the trek at Salto Hueso.

At about 9 a.m., we hoisted our packs onto our backs and set off through the

high grass towards the falls. Midway, we veered up a track at right angles on our

left and began to climb a steep grass slope onto the savannah. Ricardo pointed

out small pebbles of iron ore that littered the ground. As we neared the top,

Richard and I spotted a giant ant in the grass. It was about an inch long, jet

black and had massive fangs. Ricardo had a look at it and told us we had just

seen the infamous 'Hormiga 24' (the 24 hour ant). It got its strange name

because if it bites, the victim usually has a high fever for 24 hours and may die.

It was a formidable looking insect, and not something I wanted to get too close

to!

On the crest of the hill, there was a small churuata against the impressive

backdrop of Ptari tepui. I took some photographs using the mini tripod, and

then rested with the group under the shade of the thatched roof. Resuming the

trek, the path lead down the other side of the hill and plunged into the

rainforest. Bruno led the way, with a machete in one hand and a large shovel in

the other. Once under the tree cover, the light dropped off dramatically and it

was much more humid. We crossed several small creeks on logs, and then a

fairly wide river, this time on a high and slippery tree trunk. These difficult and

nerve wracking crossings became a regular feature of the trip, and something

that I always struggled with. My balance with a heavy pack is quite poor, and

Ricardo often carried my rucksack and camera across for me. Whilst crossing

one of the smaller creeks I saw a beautiful black butterfly, with red lines at the

edges of its wings. A little further into the forest, I saw my first hummingbird in

the wild! It was grey-white in colouration with an elongated tail and when I

consulted Schauensee and Phelps' book Guide To The Birds Of Venezuela, it

seemed most likely to have been a Grey-breasted Sabrewing. According to the

book, this bird is found in the tropical zone south of the Orinoco in the states of

Amazonas, and west and south Bolivar (where we were). Its main habitat is

rainforest, second growth, scrub and plantations. It was only visible very briefly,

as it flitted in and out of the shadows and then disappeared behind the dense

foliage. I was very happy with this sighting, because before I had set off for

Venezuela I had said that even if Angel Falls was clouded over or we didn't make

it that far, if I saw a blue morpho butterfly and a hummingbird I would consider

the trip a huge success.

Shortly after this, I saw another kind of beautiful butterfly, which flew very

close to the ground with a rapid, darting flight. Its fore wings were a dull

muddy brown colour, but the hind wings had a subtle and intricate blue and

black pattern on them. We were to see many more of this same butterfly during

the long walk to Kamarata.

A flowering bromeliad in the rainforest.

We suddenly emerged into a Pemon plantation, with a small churuata in the

middle. The path skirted the edge of the crops, and there were pineapples and

bananas growing in amongst the more usual cassava. Near to where the path cut

back into the rainforest was a thin tree with blue flowers, which Ricardo said is

a cure for malaria (and Ricardo would know, having had the disease five times).

Shortly after we had re-entered the forest, Bruno stopped and began to cut

methodical notches into a thin tree trunk with his machete. He then peeled

back the bark, which came away in one piece, and fashioned it into an extra

strap for his wicker rucksack. The bark of this particular tree is very strong, and

the Pemon often go in search of it in the forest, so that it can be used in

construction.

Once more, we emerged into a large clearing. This time it was obvious that the

Pemon had only just felled and burnt the trees, and we had to pick our way

round and over the blackened stumps and logs. A white swallow tail butterfly

fluttered past us, looking incongruous among the burnt wreckage of fallen

trees. Flowering bromeliads sprouted from tree trunks as we made our way

back into the forest, before emerging once again, this time onto the savannah.

We climbed a steep grassy slope up to a large black boulder, with views of Ptari

Tepui ahead of us, and Tirapon Tepui behind.

As the path re-entered the forest on the other side, Bruno pointed out a thin

bamboo plant, covered with fine hairs and spiked at the top where it had been

cut short by the machete of the last Indian to maintain the trail. Bruno stopped

the group, prodded it with the tip of his machete and warned us not to touch it,

or let any part of it touch our skin, otherwise the affected area would swell up

and become covered in painful welts. I made a point of memorising its

appearance, in case we came across it again.

The forest was thick and the terrain heavy going, we were all sweating heavily

with the exertion by the time we stopped for lunch by the banks of the Mari

River. The river was narrow and slow flowing as it wandered through the dense

jungle, and had got its name from the tiny sardine fish that were abundant in

its waters. On the menu for lunch was cheese, salami and bread followed by

hunks of the delicious ginger bread that Ricardo had bought in Cintillo. This was

followed by an extremely juicy orange.

It was then a two hour walk to our camp. The terrain was very difficult as we

continually ascended and descended steep, slippery slopes. While walking

through one muddy section, Bruno pointed out the first tapir tracks that we saw

on the trek. A little further on we came across a fallen tree stump that was

covered in small white mushrooms, which the Pemon often cook and eat.

Ricardo and Richard tried some raw, and I ate some later on in the camp, once

they had been cooked and dipped in the Pemon chilli sauce (which is made with

a special ingredient - termites!). Bruno also found a specific type of thick vine,

which sometimes contain potable water. He cut it in half at head height with his

machete, but at an angle so that the lower tip formed a spout. Unfortunately, it

seemed that it was too early in the rainy season for the vine to have taken up

any water, and it was dry. He tried again for us many times on the trek, but it

was always the same result.

At last we arrived at our camp, and slumped exhausted on the ground. It was

not the camp that we had been heading for, but we were not far behind

schedule. Fortunately, the framework from an old shelter was still in place, so

Bruno, Juan, David and Alejandro did not have to build from scratch. While they

tidied the clearing with their machetes, it was difficult to avoid getting in their

way, and so I decided to walk down to the small stream nearby and bathe my

feet. It was a beautiful spot, the dappled sunlight filtering down to the water

through the dense green canopy. I sat on a small rock in the middle of the

stream and dipped my feet in the cool, clear water. Suddenly, there was a loud

humming noise and I looked up to see a magnificent blue-green hummingbird

hovering just in front of my face. Janet had told me that they often come close

to inspect people, and that was exactly what it was doing. It remained still for

a few magical seconds, and then veered away behind the foliage.

Back in camp, Bruno and the other porters had put up the tarpaulin that formed

the roof of our shelter. The way that they had done it was very clever; thin

whippy branches had been split lengthways and bent at right angles over a

central ridge pole. In this way they supported the tarpaulin, and curved it so

that it would shed any rainwater. With Ricardo interpreting, Bruno explained

that they had also lashed the tarpaulin down at the edges, which is customary

in the Gran Sabana region, because of the possibility of strong winds. As it

happened, Bruno's timing couldn't have been better, because the heavens

suddenly opened and we were all forced to take shelter from torrential rain.

Bruno told us that this campsite is called Matura in the Pemon language.

We spent the evening watching the rain and chatting about the trip so far. We

all had a cup of tea to warm ourselves, and later on, polished off the rum and

coke. Dinner was a very nice meal of pork chunks, rice and vegetables which

Bruno and Ricardo cooked over a large camp fire. By half nine everyone was

quite tired, and we struggled into our hammocks for our first night in a

makeshift shelter, deep in the forest. Once cocooned in my hammock, I was dry,

comfortable and didn't find it too difficult to forget about my surroundings and

drift off to sleep. I would have benefited from warmer clothing early in the

mornings though, when the temperature fell quite considerably.

Day 5 - Tuesday 5th September.

I was awake at five once again, waiting for the dawn. Breakfast this morning

was porridge (with raisins) and coffee. As we were about to finish eating,

another Grey-breasted Sabrewing hummingbird appeared and darted around the

camp.

By about nine we were trekking once more, and got off to a slippery start on

treacherous ground. We crossed several small creeks and then a wide one, once

more the crossing was made on a slippery log. It was difficult enough to require

the use of the safety rope that the group carried. So we stopped and put our

rucksacks down, resting while the line was set up parallel to the log and at

chest height. What happened next still makes my blood run cold. As Janet leant

over to adjust her backpack, she collided with the tip of Alejandro's machete,

which was poking point first out of the top of his large wicker rucksack. Janet

recoiled, clutching her eye. Miraculously, the tip of the machete had missed her

eyeball by a matter of a couple of millimetres, and instead had been stopped by

the bone of her socket. Blood was now running into her eye and making it

difficult for her to see. She had had an incredibly lucky escape. Once we were

all safely across the river, Ricardo got out his first aid kit and examined the

wound. There was some discussion as to whether the cut might need a butterfly

suture (an alternative to stitches) to close it, but fortunately it was actually not

very deep. He dabbed some anesthetic cream onto the wound to numb the

pain, and the bleeding stopped shortly after. Janet had been remarkably calm

during the whole episode, and it was only once we were in camp in the evening,

and she saw in a mirror how close she had come to losing her eye that she

realised the full seriousness of what had happened. Just along the trail from the

river was the clearing where we were to have camped last night, so we rested

there for a while to allow Janet to recover. When we set off again, Alejandro

adjusted his machete so that the blade was enclosed by his rucksack. He was

feeling very guilty about the whole business.

The trail ahead climbed very steeply through thick vegetation, before topping

out briefly on the savannah. Just as we were about to leave the forest and step

into the sun, Bruno pointed out a small plant with elliptical leaves. At the base

of each leaf stalk was a bulbous node at the junction with the main plant stem.

Bruno cracked open one of these nodes with his fingers and lots of tiny red ants

came streaming out. With Ricardo interpreting, he explained that the plant and

ants live in symbiosis. The plant provides shelter for the ants, while the ants

protect the plant from other predatory insects that would eat its leaves.

Once out on the savannah, we had a glorious rest in the hot sun, during which

Bruno found a tiny orchid with delicate red flowers. Our respite from the dank,

dark forest was all too brief and we were soon back in the thick of it. We

trekked for roughly another half an hour, over a couple of very pretty jungle

streams, and into a clearing where we stopped for lunch. It was a lovely spot by

a small river, and we could see the top of the canopy overhead. As I was looking

up at the trees, a huge blue morpho soared through the tree tops.

Lunch was basic, just cheese, salami and bread once again. By this stage of the

trek I found that I had already become very hungry the whole time. While we

were eating, Bruno took an empty can and placed it on its side at the bottom of

the shallow stream. He said that it was often possible to catch freshwater crabs

in this way, but unfortunately none appeared. The Pemon often use a much

more spectacular method of fishing that Ricardo had told us about. There is a

tree in the forest called Barbasco, from which they harvest pieces of bark. This

is then ground up, and thrown into the water. The bark has a potent effect and

within seconds it stuns all of the fish nearby, which float to the surface. It is a

powerful toxin, which works by interfering with respiration in the gills of the

fish.

Trekking once again, we heard the piercing call of a bird called the Screaming

Piha. It started with a short, rising note and then ended with a long falling one.

The bird itself is elusive, seldom seen and is a rather unspectacular muddy

brown colour. For the rest of the trek, it seemed that there was hardly a time

when we couldn't hear the maddening call of a Piha - it was a sound which could

really wear on your nerves. It was also at this time that we heard a bird call

that was exactly the same as the whistling noise made by a falling bomb. I

started to imitate the noise, in the hope it would do it again. However, Bruno

said not to try and copy it because it would make me very ill. At first I thought

that this must be a Pemon superstition, but suddenly realised that Bruno was

right. If you tried to make the same noise continually while trekking, you would

run out of breath and probably faint!

We were now on the fringe of an area of the forest that had been hit by a

violent storm in 1995, which had knocked over many trees. As a result the

trekking was very tough, because we had to climb over fallen tree trunks at

frequent intervals. By now though, I was using my trekking pole to steady

myself over the difficult ground. It really made a difference, especially when

descending steep, slippery slopes. An extremely hard climb lay ahead, and as

we laboured up the gradient we came across two hormiga 24 nests. Just one of

these insects was formidable enough, and a whole nest of them was a truly

frightening concept. The nests were black mounds of earth, built round the base

of two thin tree trunks. I noticed a curious thing, the rain had reacted with

something inside the nest, with the result that it oozed and foamed a bubbly

froth.

At the top of the hill the forest was more spaced out, and really quite airy.

From here, Auyantepui could be glimpsed for the first time, although it was just

a hazy ridge on the horizon. Bruno remarked that if the forest had been this

spaced out all the way, we would have been in Kamarata by now.

The trail now lead largely downhill to the camp, which was at a place which the

Pemon call Topia. On the way we came across a tiny clearing in which a clump

of unusual plants were growing. The long thin leaves sprouted directly from the

ground, and were banded with black markings. Bruno said that they were known

to the Pemon as 'jaguar tails'. Fortunately, it was only a short distance from the

jaguar tails to the camp, and I was glad, because I could feel a blister coming

up on the underside of my toe. Blisters were my major dread on the trek,

because I knew that there would be a point when all of my hiking socks would

be soaked (my boots were totally wet by this point) and my feet could be ripped

to pieces by the constant pounding of the trail. My feet had to get me to

Kamarata, then we would be relaxing in the boat as we motored towards Angel

Falls, and they would have ample time to recover.

Arriving in the camp clearing, we could see that our shelter would have to be

built from scratch. There was an existing framework, and even a tiny thatched

area, but they were extremely rotten and liable to collapse at any moment. The

frame certainly wouldn't have supported the weight of ten people and their

hammocks! While Bruno and the porters went to work, David had been asked to

lead us all to the river where we could swim and wash. It was only a short walk,

out of the camp, over a river on a high log (David set up the safety rope for us)

and then down the steep bank to the main river. At the point where we emerged

there was a wide rock shelf that lead to a deep pool - perfect for swimming.

However, a nasty surprise was in store for anyone who was a bit too eager to get

to the water (as I was), the rock was as slippery as an ice rink and as I moved

out across it, my feet flew out from under me and I landed painfully on my

back. I picked myself up, and then inched carefully into the water. I plunged in

with all of my clothes on, because I wanted to rid them of the smell of mildew

and rot that had begun to set in from the ever present damp of the jungle. I

climbed out of the water after my swim and knelt on the rock ledge to wash my

hair and then shave. Ricardo had found an even better spot for swimming just

upstream, so we followed him along the shelf and came to a beautiful wide

pool, fed by a fast but shallow waterfall. A large tree trunk had fallen across

the width of the pool, making an excellent 'diving board'. We soon discovered

that it was possible to slide down the waterfall on your backside, until you were

swept into the middle of the pool and could grab hold of the tree trunk.

Ricardo, Richard and I took it in turns to shoot the rapids, or jump off our

jungle diving board. It really was a fantastic place and I felt that we had arrived

in a tropical paradise.

Back at the rapidly developing camp, we had just finished changing out of our

wet things under the rotten thatched shelter when it dramatically collapsed

without warning. Luckily we all managed to scramble clear, but then had to dig

out our rucksacks. Richard and I were still sorting out our kit, when Bruno asked

us if we would like to go hunting with him. We didn't need to be asked twice, as

we both knew that even if we caught nothing it would be a highlight of the

journey. It was a frantic dash to get ready, and I wasn't exactly sure how long

we would be gone or what to take. In the end, I settled for a jumper, head

torch, camera and also my large survival knife which was on my belt. Bruno had

a large head torch and his single barrel shotgun, with spare cartridges. After

posing with Bruno for the obligatory 'hunting party' photo, we slipped quietly

into the twilight.

Bruno lead the way back up the trail to the jaguar tail plants, where we turned

left ninety degrees and pushed into the forest. Richard and I walked as quietly

as our unfamiliarity with the rainforest would allow, while Bruno's shotgun

barrel pointed alarmingly in our direction. "You can go in front of me",

whispered Richard.

"Why's that?" I said.

"Because I don't want to get my f***ing head blown off", he replied, in a very

matter-of-fact manner.